By: Austin Dewey

Reliable energy is a commodity that every American has grown accustomed to. Whether plugging in our toasters in the morning to make the perfect bagel sandwich, maintaining comfortable temperatures in our living spaces during the winter, or being held on a ventilator at the hospital, having a reliable energy grid is essential to our society. Additionally, as we combat the current climate crisis, America has expanded its green energy infrastructure to where renewable energy generates over 20% of our electricity. [1] While this may sound like a promising step toward a sustainable future, our aging energy grid and infrastructure are running into a higher risk of failure with every green advancement, particularly with solar energy. This dilemma has been described as the Duck Curve Problem.

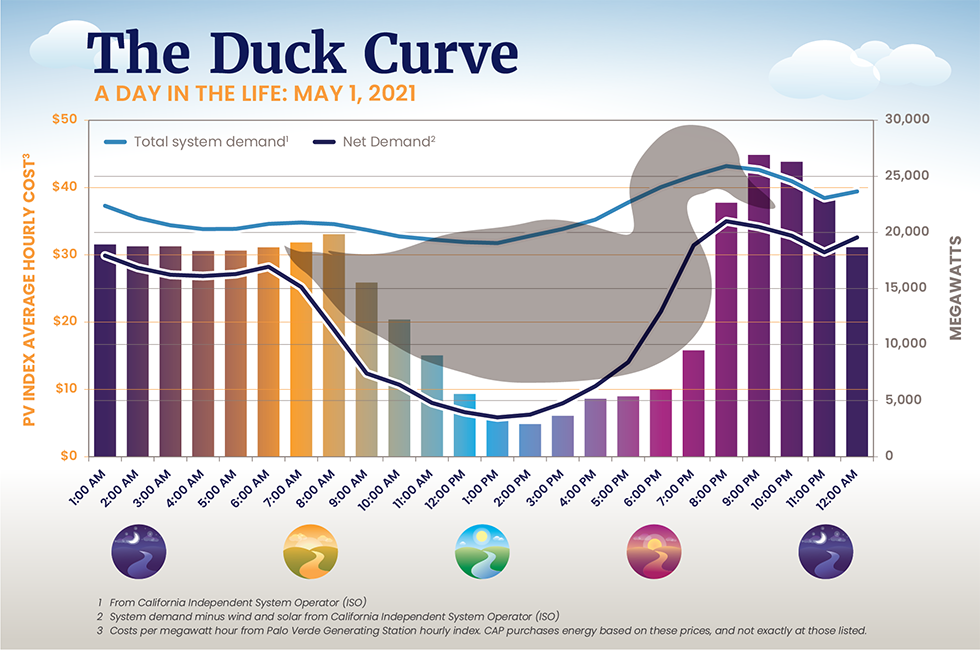

The top line of this graph represents the grid’s energy demand from nonrenewable sources over 24 hours, while the bottom line shows the demand when solar renewable energy is factored in. The significant drop in midday energy demand provided by solar energy, contrasted with the sharp rise in the evening, creates the famous ‘duck’ shape seen in the graph. This steep and quick rise in energy demand puts huge strains on nonrenewable power plants which risk overgeneration to compensate for the energy use differential. This imposes higher prices on consumers, causes infrastructure damage, and threatens our national security.

To curtail this problem, the Biden Administration, under the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), has launched a joint grid modernization initiative with twenty-one states toupgrade approximately 100,000 miles of existing transmission lines. [2] This will allow for advancements in battery technology, which will help store midday solar energy and allow for a gradual release of energy when the sun goes down, which will reduce the strain on power plants. Recently, the California Energy Commission has used IIJA funding to expand 100 miles to their power grid to allow multiple sources of renewable energy input such as wind and hydroelectric, to reduce the effects of the duck curve. [3] This is an effective solution because hydroelectric and wind energy input will buffer the drastic evening energy demand.

While the IIJA is a critical step toward enhancing the reliability of the U.S. power grid, further state-level legislative action is needed to meet renewable energy goals without posing a threat to our energy grid infastructure. California’s Energy Storage Mandate serves as a key example. This innovative mandate requires the state’s three major utility companies: Pacific Gas and Electric, Southern California Edison, and San Diego Gas & Electric to procure a combined 1,325 megawatts (MW) of energy storage over ten years. [4] This initiative has proven highly successful, as all three utilities have nearly met their procurement targets. [5] By expanding energy storage capacity, this legislation ensures more efficient use of renewable energy, reducing strain on the grid and helping to stabilize electricity prices during periods of high demand.

As we continue to expand renewable energy and modernize our grid, innovative green legislation in energy storage will be essential to overcoming the challenges of the Duck Curve and ensuring a reliable, sustainable future for America’s energy infrastructure.

____________________

[1] Renewable Energy, U.S. Dep’t of Energy, https://www.energy.gov/eere/renewable-energy (last visited Oct. 5, 2024).

[2] Biden Administration Partners with 21 States on Grid Modernization Initiative, S&P Glob. Commodity Insights (May 29, 2024), https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/latest-news/electric-power/052924-biden-administration-partners-with-21-states-on-grid-modernization-initiative.

[3] California Receives More Than Half a Billion Dollars in Federal Funds to Improve Power Grid, Off. of the Governor of Cal. (Aug. 6, 2024), https://www.gov.ca.gov/2024/08/06/california-receives-more-than-half-a-billion-dollars-in-federal-funds-to-improve-power-grid/.

[4] Cal. Assem. B. 2514, ch. 469, 2010 Cal. Stat.